The final entry of this blog series has arrived. This week will focus on the financial side of improving maternal health in the United States (U.S.). Due to the current situation, this discussion is going to look a little different. We are in unprecedented times when funds are being allocated toward the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and unable to be put toward other bills. The country is understandably at a standstill.

I had the opportunity to interview Arizona State Senator Heather Carter this week, courtesy of the quarantine popular Zoom. We discussed maternal health and two bills that she has sponsored, S.B. 1290 and S.B. 1392, both of which promote the health of mothers in Arizona. S.B. 1290 would establish a Maternal Mental Health Advisory Committee in order to recommend improvements for screening and treating maternal mood and anxiety disorders. S.B. 1392 extends Medicaid health coverage for women up to one year postpartum (Arizona State Legislature, 2020). Both of these bills would have made a significant impact on mothers within the state. When discussing the future of these bills, Sen. Carter stated, “we had huge support, everybody said they wanted in, and then it didn’t get included in the skinny budget. Now it looks like we have a billion-dollar deficit, so there’s no way that is going to get done.” Due to the current state of Arizona, the country, and the world, priorities have changed.

Sen. Carter discussed how she is “super passionate about maternal health and maternal mental health” and has been “working on these issues over the years.” It was clear that she is disappointed she will not be able to follow through with the positive momentum she has created this year in impacting maternal health. Speaking in reference to maternal mortality and morbidity, “it’s shocking that we have these numbers, not only across the country in a first world country, but in Arizona specifically. Disproportionately. There is so much more we need to be doing.”

“This year I said I am going to shine a bright light on the lack of access to care in Arizona for our moms, every single solitary corner… let’s look at it and figure it out.” There were new ideas and solutions on the horizon.

“We went through everything from workforce development issues to not having enough providers. We have one whole county on the east side of Arizona that has no OBGYN nurse practitioners, doctors, nothing. They have to drive six hours into [the city] to be seen. It’s so bad.” She continued on to explain that they examined the workforce, training, and current available services to discover every issue this state currently had.

“We’ve been talking about this stuff for years. It’s been one little bill here and one little bill there.” Instead they decided to put in all together in one “mom and baby package.” We had this great tsunami of support and then COVID-19. So now I have no idea what is happening, I don’t know what we will be able to do this year. Nothing.”

So, where do we go from here?

She made it clear, “the need and the interest are still there. We just don’t have any money.”

The last few months I have focused on the U.S. as a whole, and while this interview primarily focused on Arizona, this problem currently exists across the nation. This discussion made me wonder for how long into the future will this pandemic affect the U.S.? Will the financial ramifications carry on into the next legislation? Will it continue to stall all of the needed bills? Will funding continue to be allocated? How will the health of the nation suffer indirectly from COVID-19?

We must continue to fight for investment in maternal health. Investing in women’s health has been shown to contribute to more productive and better-educated societies. In fact, the development and economic performance of nations relies on how each country protects and promotes the health of women, before, during, and after childbirth (Onarheim, Iversen, & Bloom, 2016).

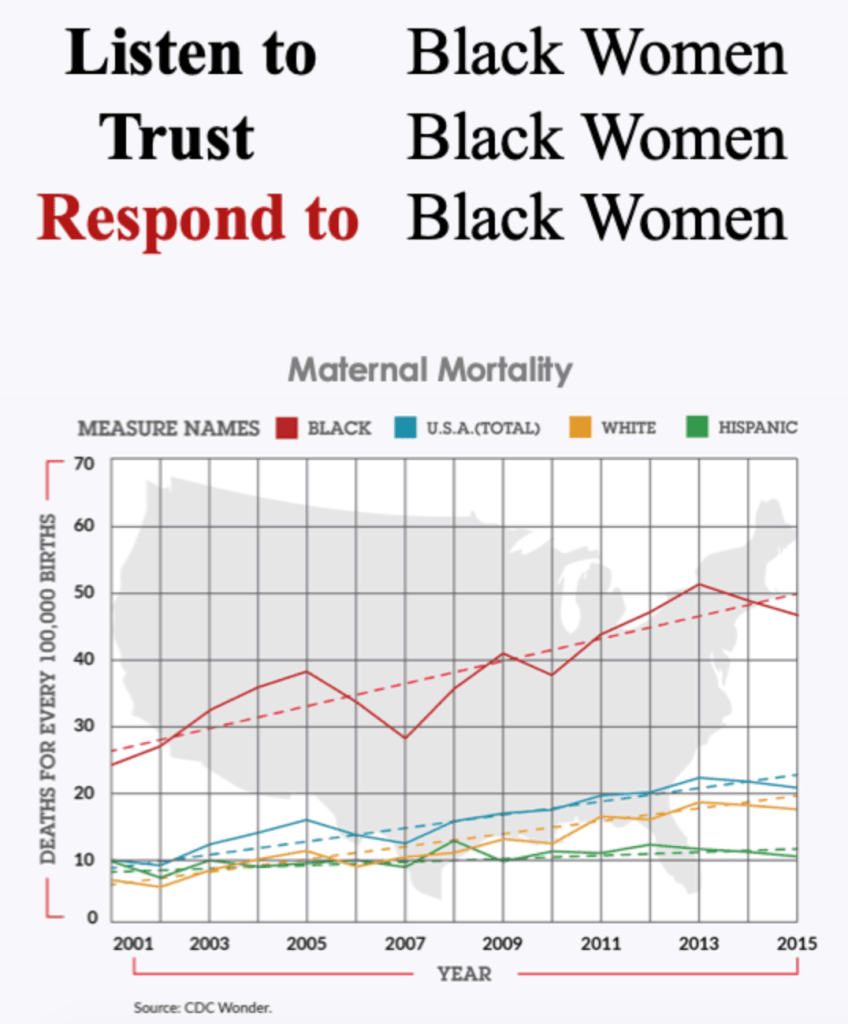

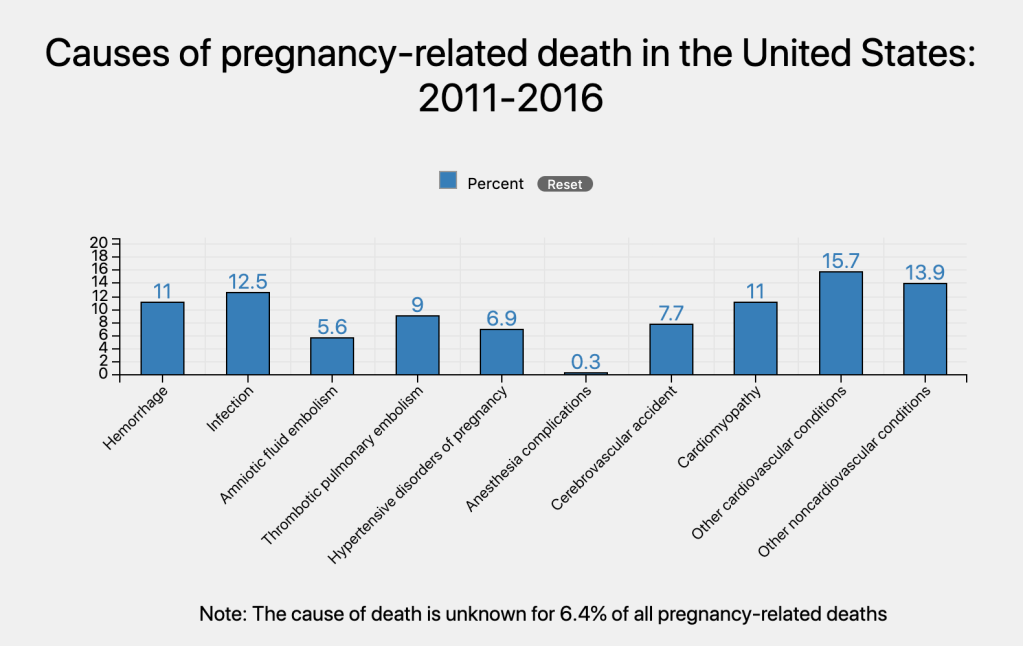

I have brought up the statistics multiple times, but I must draw your attention to them one more time. The U.S. has the highest maternal death rate among developed nations in the world with approximately 700 women dying every year due to pregnancy related complications. Up to 60% of these maternal deaths are PREVENTABLE. For each of these women who die, up to 70 suffer from avoidable complications that result in near death. The annual cost of these near deaths to the mothers, their families, taxpayers and the healthcare system runs into the billions of dollars (Anderson & Roberts, 2019)

The U.S. spends more on health care than any other country in the world but has poorer population health outcomes (Feldscher, 2018). This is evidenced by the statistics I just mentioned. Sustainability relies on us changing our focus. Prevention is key. Implementing the solutions that I have addressed in this series to prevent maternal mortality, such as technological advancements, including bringing telehealth services to rural and underserved areas and utilizing tracking systems to identify areas that need improvement, creating programs for healthcare professionals to identify and address biases in care, training providers to work in rural areas, and increasing access to care through increased Medicaid coverage through pregnancy and for up to one year postpartum. Rather than paying billions of dollars for the result of maternal morbidity and mortality, we can invest those dollars into prevention and health maintenance for all moms.

References

Anderson, B. A., & Roberts, L. R. (2019). The maternal health crisis in America: Nursing implications for advocacy and practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Arizona State Legislature. (2020). Bill status inquiry. Retrieved from https://apps.azleg.gov/BillStatus/BillOverview

Feldsher, K. (2018). What’s behind high U.S. health care costs. The Harvard Gazette. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2018/03/u-s-pays-more-for-health-care-with-worse-population-health-outcomes/

Onarheim, K. H., Iversen, J. H. & Bloom, D. E. (2016). Economic benefits of investing in women’s health: A systematic review. PloS One, 11(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150120